A.I. Wants Its Money Back

Building a techno-utopia is proving to be a slower and more destructive business than we thought. Here come A.I. ads, porn, and video slop.

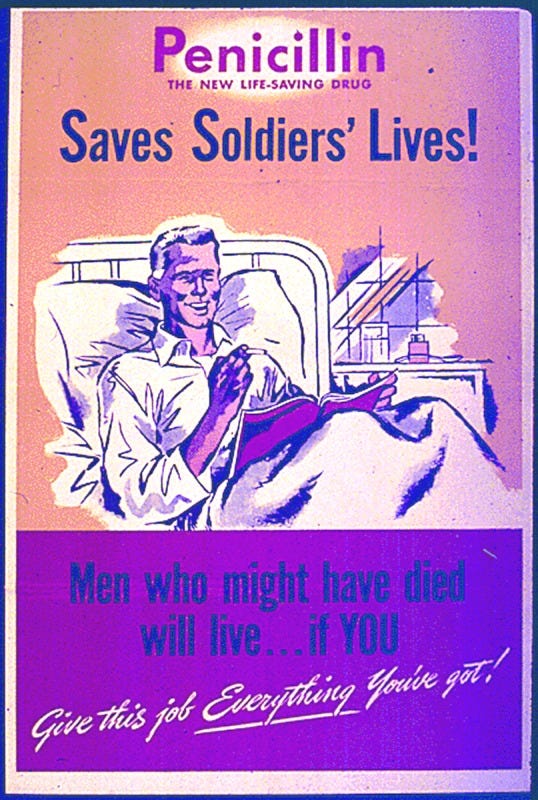

At the beginning of the 20th century, death on the battlefield was a nightmare.

A bullet passing through clothing carries shreds of the material into the body, and without infection-fighting compounds at their disposal, surgeons could do little more than burn flesh with painful antiseptic and amputate. In a speech to the Royal Institute in 1915, surgeon Richard Godlee described the infecting horrors of trench warfare, where “if a man is hit, he often falls into filthy mud and water… and the water is hopelessly polluted, and soaks his clothes and his wound.” This was a real problem in need of a real scientific solution.

Then, between 1941 and 1946, as America entered another global conflict, the US Government funded the creation of a miracle cure. The compound known as penicillin had been known to inhibit bacteria in lab experiments since 1928, but wasn’t considered a medication. Then a pair of Oxford scientists visited the US and demonstrated that, using makeshift production equipment and some new forms of penicillin-producing mold they’d refined, the stuff could fight infection in humans. As a University of Utah history describes it, in just five years, thanks to the Office of Scientific Research and Development, something typically grown in bedpans and milk bottles was being produced in 10,000-gallon tanks, and “a little-known, clinically insignificant, and unmanageable compound became a mass-produced miracle.”

The leaders of the companies building foundational A.I. models have promised for years now that their technology is taking us toward a utopian future that will make any short-term difficulties worth it. Here’s how Sam Altman described the theoretical trade-off this year:

There will be very hard parts like whole classes of jobs going away, but on the other hand the world will be getting so much richer so quickly that we’ll be able to seriously entertain new policy ideas we never could before…Although we’ll make plenty of mistakes and some things will go really wrong, we will learn and adapt quickly and be able to use this technology to get maximum upside and minimal downside.

His public statements on the subject, like those of most A.I. leaders, have near-religious certainty to them. According to this faith-based logic, the threat of job loss will be worth it. The payoff is undetectable, but the job loss is already here. Due to the efficiencies offered by automation, Amazon, the nation’s second-largest private employer, is laying off 30,000 corporate employees this week, and according to the New York Times plans to eventually cull more than 500,000 of its 1.2 million workers.

The rise of mental-health crises connected to chatbot use will somehow be worth it. OpenAI this week released its findings that 0.15% of users (1.2M people) are showing signs of heightened emotional attachment to ChatGPT, the same number “have conversations that include explicit indicators of potential suicidal planning or intent,” and 0.07%, or roughly 560,000 people, show signs of psychosis or mania in their conversations with the product.

And the destruction of traditional education will supposedly be worth it. Roughly 84% of high school students now report using generative AI to do their homework, and teachers have more or less given up on homework. "They’re not doing it,” an Inglewood English teacher told the LA Times. As one college professor recently told me, his number-one challenge is convincing his incoming freshman that there’s a difference between having read the assigned material and having read a chatbot’s summary of that material.

So is the promised utopia close at hand? A much-discussed recent MIT Media Lab study found that 95% of companies polled — the sorts of companies laying off workers on the assumption that A.I. will soon be able to do the work in their stead — have found that while A.I. tools improve individual productivity, they deliver zero measurable return on investment. And OpenAI cofounder and former head of A.I. at Tesla Andrej Karpathy said this month that Artificial General Intelligence — the sentient, smarter-than-human form of the stuff that’s supposed to make our struggles worth it — is at least a decade away. That’s a long time to be unemployed, in mental crisis, and out of school.

And that’s assuming that A) AGI will unlock utopia and that B) we’re even on a path to it. The promise of AGI is impossible to weigh, but experts are increasingly pessimistic that LLMs will lead us there. As David Bader, director of the institute for data science at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, told the Guardian this summer

“We need to distinguish between genuine advances and marketing narratives designed to attract talent and investment. From a technical standpoint, we’re seeing impressive improvements in specific capabilities – better reasoning, more sophisticated planning, enhanced multimodal understanding.

“But superintelligence, properly defined, would represent systems that exceed human performance across virtually all cognitive domains. We’re nowhere near that threshold.”

In the meantime, however, the estimated trillion dollars poured into A.I. so far is something the companies are under increasing pressure to pay back. And while antibiotics were a real human problem in search of a solution, this moment is where companies tend to invent solutions in search of a problem. This is why we’ve begun to see the heads of companies like Google talking openly about integrating advertising into the lifelike conversations its chatbot Gemini conducts. This is why OpenAI, although Sam Altman has decried the attention economy in the past, is moving to upend social media with Sora 2, its product that generates 10-second A.I.-generated videos that, among other things, steal the likenesses and voices of historical figures. (According to reporters at The Information and at The New York Times, this is a choice that runs so contrary to the stated world-improving goals of the company that employees there are openly airing their discomfort.)

As I argue in my book The Loop: How A.I. is Creating a World without Choices and How to Fight Back, A.I. is the first world-transforming technology in modern history that has been developed and governed entirely by private companies, rather than by public institutions or government agencies. And as a rule, companies are not in the utopia business.

We don’t know whether A.I. leads where its creators say it will. But we do know what tends to happen when world-improving innovations are forced to justify themselves to investors.

Today, left to the whims of the open market, antibiotic development has more or less ceased. Where once a nationalized effort coordinated work among 57 agencies and a dozen allied governments to make doses of penicillin available to anyone who needed them for fractions of a penny, the commercial pressures of private-sector drug development have caused the major drug makers to abandon the search for new antibiotics almost entirely. The reason is, of course, money: as a Nature analysis reports, a new antibiotic costs $1.5 billion to create. The average annual revenue it offers its creator is less than $50 million. “That’s tiny and nowhere near the amount needed to justify the investment,” the chief executive of Novo Holdings, an investment firm in Hellerup, Denmark, focused on the life sciences, told Nature.

It may be that someday a robot intelligence will be capable of solving our problems (and antibiotic development is, in fact, one of the problems experts hope it can help with, although the indications are at the moment that it can’t do it at the savings that would jumpstart the field again). But we know that for the moment, as it has always been, for-profit companies are hemmed in by their fiduciary responsibilities, and invariably have to follow them wherever they lead. The economics of protecting humans against their vulnerabilities don’t typically lead to much of a profit. The profits expected in the race to build A.I. — no matter how lofty the long-term goals — are already leading companies to begin experimenting with making money off our vulnerabilities instead.

Recommended Reading

If you aren’t already a subscriber, I highly recommend signing up for Nita Farahany’s excellent Substack, where she is absolutely killing herself to bring subscribers a weekly summary of her extraordinary Duke Law School course in A.I. and its dangers. Her most recent post lays out a framework for evaluating whether a model is harmful, or manipulative, or both, and it’s absolutely riveting.

The Podcast

The most recent episode of The Rip Current is a conversation with the very courageous Brazilian disinformation reporter Cristina Tardaguila, who escaped her native country after her work exposing the propaganda of Jair Bolsonaro earned her death threats there. We discuss the shocking conviction of the former Brazilian president for the same actions the U.S. president took in 2020, and how the new hostility toward Brazil from the Trump administration is going to drive that nation into a deep and long-lasting alliance with China and Russia.