"Good Luck Waiting on Hold, America"

Interviews with the experts fired from CFPB, the agency built to protect you against being cheated, reveal the scams you'll now have to look out for.

Nick Hand is exactly the kind of person Big Tech hires.

An astrophysics PhD from UC Berkeley — I so often see physics degrees in tech executives — he says many of his classmates are now “high up at Google and Meta.” For him “that route was an option, and I decided against it early.”

Why?

“Pretty early on I saw the ways that Big Tech and Silicon Valley and these tech companies were creating an unfair playing field. They were ahead of the curve and even before AI was AI they were using machine learning to collect data on people, surveil them, and all of that didn't feel right. I didn't want to work every day to make Facebook a little more money,” he told me.

“I loved my PhD, I loved my research” — and tech companies have made an art of providing comfortable “campuses” for people who want to continue that life — “but I wanted to have an impact.”

After time as a data analyst in a city controller’s office, helping to conduct audits and root out waste and fraud, he was hired in September 2023 as part of a new elite group of technologists at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which created a pool of skilled researchers that CFPB and other agencies could draw on to do battle on behalf of Americans against the growing number of scams, amplified by technology, that are taking money out of our pockets.

And of course that’s what makes CFPB exactly the kind of agency Big Tech hates. Mark Zuckerberg complained about it by name in his recent Joe Rogan interview, in which he talked about leaning away from the left after coming under new regulatory and political pressure.

ZUCKERBERG: We had organizations that were looking into us that were like not really involved with social media like I like the CFPB like this um Financial…I don't even know what it stands for…it's the it's the financial organization um that Elizabeth Warren had set up—

ROGAN: Oh great.

ZUCKERBERG: —we're not a bank, right? It's like “what does Meta have to do with this?” But they kind of found some theory that they wanted to investigate and it's like okay clearly they were trying really hard right to to like find find some theory. But it, like, I don't know it just it kind of like throughout the party and the government there was just sort of, I don't know if it's—I don't know how this stuff works I mean I've never been in government I don't know if it's like a directive or it's just like a quiet consensus that like we don't like these guys they're not doing what we want we're going to punish them— but it's tough to be at the other end of that.

CFPB was first proposed by Elizabeth Warren as a Harvard Law Professor in 2007, as the mortgage crisis consumed American homeowners, and Congress installed it in 2011, over the objections of Republican lawmakers. It specifically seeks to protect the finances of consumers, but unlike the Federal Trade Commission, it does it in a public way, with millions of complaints available for anyone to read and analyze, and open publication of its enforcement efforts. As an executive at a banking trade group complained to Congress in 2017, “once the damage is done to a company, it’s hard to get your reputation back.”

For years tech executives have rolled their eyes at the notion of being regulated by the olds of Washington, often short-handing their impatience by referring to Zuckerberg’s 2018 Senate examination by Senator Orrin Hatch, who didn’t seem to understand at the time how Facebook made money. “How do you sustain a business model in which users don’t pay for your service?” Hatch asked innocently. “Senator, we run ads,” Zuckerberg replied, to laughter from the gallery.

But as elected officials recruited tech-savvy staffers, and agencies like CFPB hired more people like Hand, regulators have become newly effective. (I’ve been talking about this trend for a while.) Lina Khan, head of the FTC, was so aggressive that even Kamala Harris’s corporate backers urged the candidate to fire Khan should Harris win office, a sure sign of her effectiveness. (Political support from business is inevitably contingent on staying out of its way, as I’ve written.) So it’s no suprise that when President Trump invited the CEOs of tech companies to attend his inauguration, most of the executives gathered on the dais were the heads of the very companies CFPB has been looking into, especially as most if not all of them move into financial services. As one CFPB technologist put it to me this weekend, “You’d be hard-pressed to name a big tech company that isn't trying to get into financial services or fintech and isn't also subject to some sort of examination by CFPB.”

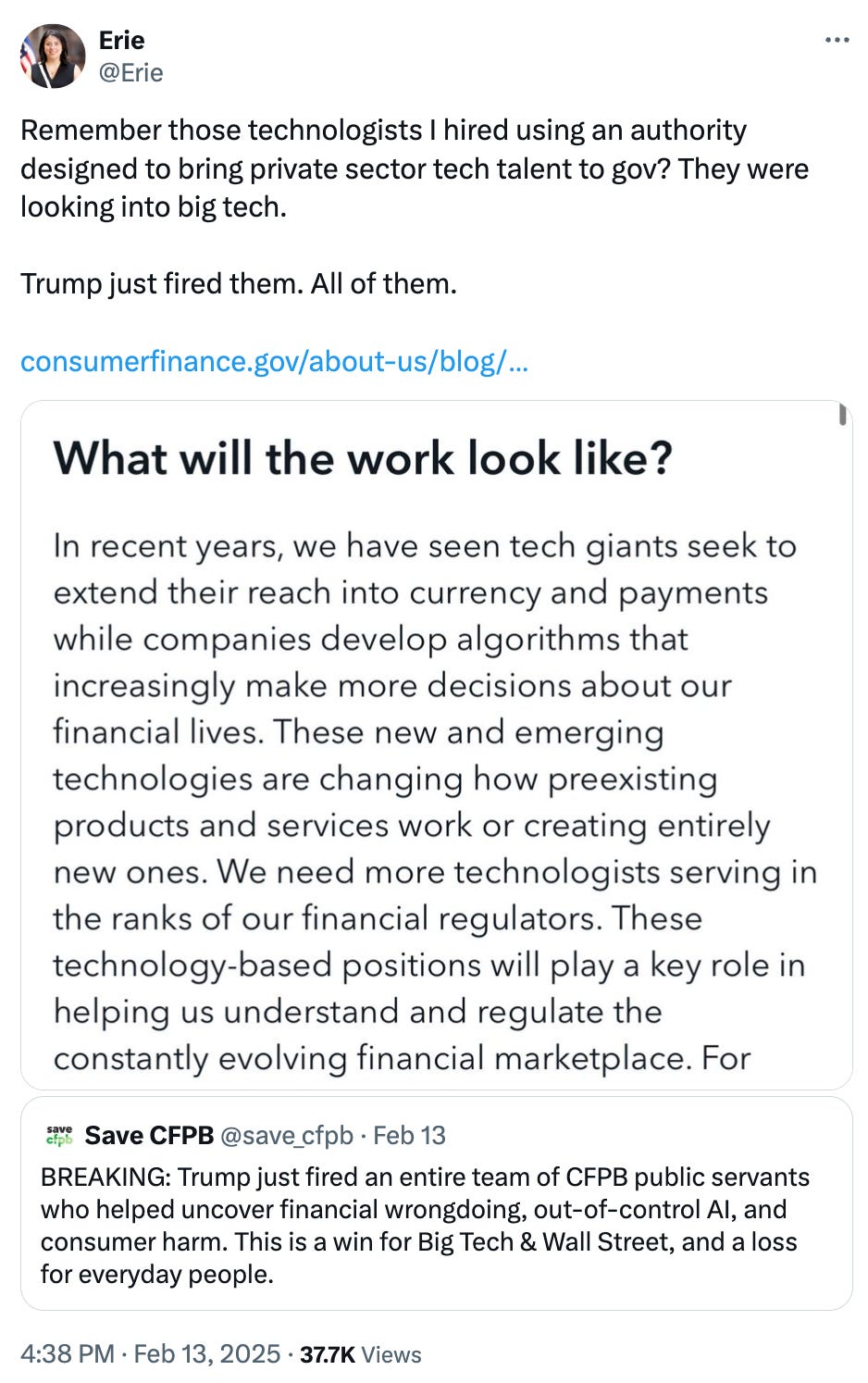

The 100 people fired from CFPB on Thursday, before a federal judge halted more dismissals, included the 20 or so technologists like Hand who were the backbone of its research and investigative powers. They reported to Erie Meyer, the bureau’s Chief Technologist, who described the dismissals this way on X:

The folks at CFPB I interviewed this weekend did their best to keep their reactions even and professional, but they’re clearly outraged. (And while Hand was willing to be named, the rest asked for anonymity. You can see how I handle these requests here.)The text of the dismissal notices, signed by chief operating officer Adam Martinez and shared with me by their recipients, gave only the briefest rationale:

The purpose of this memorandum is to notify you that your employment will be terminated effective at the close of business on February 13, 2025, due to Executive Order implementing the President's "Department of Government Efficiency" Workforce Optimization Initiative – The White House dated February 11, 2025.

My conversations with CFPB insiders like Hand raise at least three important questions. Let’s work through them.

Does firing these technologists achieve government efficiency?

We can dispense with this one pretty quickly:

The 2025 fiscal-year budget of the CFPB is $823 million.

It has collected, on average, $1.5 billion each year since its inception.

In the simple terms of business, that’s an unheard-of 45.13% profit margin.

If we can agree that the function of the CFPB is to protect you against and punish companies for financial deception and fraud while spending the least money possible, it was enormously efficient in doing so. A federal pioneer in new processes and new hiring standards, the CFPB is, according to one technologist, “one of the most efficient agencies the federal government has.”

Was CFPB full of waste and fraud?

Elon Musk has alleged criminality and corruption throughout the government agencies his DOGE team has been disassembling, but CFPB personnel are held to an extremely high standard when it comes to conflicts of interest. The people working there are not only personally forbidden from making any investments in companies even related to the ones they might investigate — a vast “prohibited holdings” list updated regularly — their families and associates are also subject to those rules.

“And I have to undergo that review every year,” one technologist told me. “I have to report everything I do outside the job, including volunteering, and get approval. Transparency and over-communication are held in really high esteem.”

Meanwhile, as Elon Musk’s unofficial group DOGE makes these firing decisions — he posted “CFPB RIP” on X last week — it’s worth considering his conflicts of interest with this regulator. As one technologist put it, “Tesla's auto loans, the payment processor that's being integrated into X, those are inside CFPB's remit. Elon Musk would love to be able to operate in an environment where there are fewer rules. The CFPB would have been the source of many of those rules, so scuttling it directly serves his interest in those markets.”

Meanwhile Musk hasn’t made the public financial disclosures the executive branch typically requires.

What should you watch out for now?

My interviews this weekend suggest that without skilled technologists looking into banks and tech companies on your behalf, the financial landscape could quickly fill with predatory schemes and deceptive marketing. Here’s what they told me we should watch out for, in their words.

Companies Ignoring Criminal Schemes

“We saw a number of data breaches last year, including at mortgage servicing companies. We're also seeing fraudsters use AI to come up with really effective scams and phishing efforts. These companies are not incentivized to have fraud controls or to use AI to protect consumers. The incentives all push fraudsters to innovate, not on the banks and tech companies to fight it.” In January the CFPB sued Zelle, the digital payment system jointly operated by Bank of America, Capital One, JPMorgan Chase, PNC Bank, Truist, U.S. Bank, and Wells Fargo, for failing to adequately warn and protect customers against scams on the platform that amounted to hundreds of millions of dollars. Without the bureau, companies might choose to simply ignore those scams instead.

No One Answering the Phone

“Customer service is the biggest direct way people are going to experience what's coming, in the sense that certain big companies are [already] terrible to work with when you have an issue, and that's going to get worse as companies learn how to cut costs and see in the data that certain issues aren't worth fixing, because you'll stick with them anyway.”

“This is the America Elon Musk has in mind,” one technologist told me. “Good luck waiting on hold, America.”

Being Spied On

“One realm that has been under-regulated and has been coming to light recently and was about to change was data privacy. Most of the big tech companies make a boatload of money through customer surveillance. I'm not even saying they shouldn't be allowed to do that, there could be good guidelines on that, and the CFPB could have set appropriate safeguards to curtail the more aggressive data collection and privacy violations. Particularly with the advent of AI and the data needs that exist there, it's a wild west that needs to be dealt with. If it remains a wild west, who knows what's coming?”

Mortgage Mistakes No One Will Fix

“We know how unwilling a company is to give you customer service even when they might lose you as a company. A mortgage servicer, which is assigned to you randomly, when they make a mistake they have no incentive to correct it except when we make them do that. We're getting people back their money directly.”

Financial Agreements You Can’t Trust

“Look at our public case against Capital One — if you're a consumer, you’re tricked out of cumulatively billions of dollars you were told you'd be getting. Not being able to trust what a bank tells you about what you’re signing up for, credit-card rewards not being given the value you were told they have…Literally CFPB litigation is a lot of companies that have straight up lied or deceived consumers, misrepresenting simple facts about the product.”

Student-Loan Shenanigans

“Without CFPB there's a marketplace where student-loan servicers are pushing you into more expensive repayment options, and illegally keeping you from finding out about more affordable repayment options. You're being crushed under a mountain of debt, and the company you're using to pay your student loan is tricking you into paying them more money on top of your loan. Without CFPB there's not enough resources to go after that.”

Beyond these direct risks to you and me, there are larger implications of DOGE operatives working to gain access to confidential data across government (including, on Monday, IRS data on any American who has ever filed a tax return). In CFPB’s case, that data could do enormous damage, not least to the companies themselves. CFPB, in its investigations, regularly collects confidential information from companies, including their source code, their years- or decades-long strategies, and their internal communications. If DOGE operatives were to use that to benefit themselves, Musk, or a competitor, it could be a mortal risk to the company in question. As one technologist described it, “If you were interested in entering the financial services business,” — Musk launched a partnership with Visa to do exactly that back in January — “CFPB's data is about as sensitive as you can think of.”

Another form of damage is to competition. Without CFPB keeping large, entrenched players from unfairly locking you into their services, smaller players might have an impossible time entering the market. “If you get rid of the regulator that creates competition,” one technologist told me, “you can imagine that only the first or most highly funded companies will get in, and then they'll throw up all sorts of barriers.” And, as this person pointed out, that will hurt even the entrenched players in the long run. “There's a reason the big tech companies have so many acquisitions. You can't say that the destruction of the capacity of small companies to exist is good for big companies, it cuts off a major lever of innovation, which is acquisition.”

In the meantime, technologist Nick Hand and his colleagues are waiting to see whether the courts or their union can keep them employed at the CFPB. “I am looking for new jobs,” he admits. “Our union is fighting for us — shoutout to Chapter 335 — but it's an uphill battle for sure.” So is it time to cash in, take what he knows over to the companies he’s been looking at all this time? “Public service has always been what I'm most interested in,” he says. “So if it's local or state level, or a nonprofit, now more than ever it's going to be necessary to have folks with tech expertise keeping an eye on these companies.”

billionaires who whine always get my sympathy.